“Did you see anyone with bags?” My friend is looking around, increasingly frantic. “We need to find bags, right now.”

“Did you see anyone with bags?” My friend is looking around, increasingly frantic. “We need to find bags, right now.”

We’ve been at Book Expo America 2013 for an hour, and the stacks of books we’re carrying are already beginning to overflow our arms. When publisher representatives spot a media badge, their response is something like a mugging in reverse: before we can protest, we’re loaded up with catalogs and volumes.

“I have to carry this home,” I tell a publicist trying to thrust a hefty hardcover at me. “Are you on NetGalley? Can you give me a download code instead? If I give you my card, can you send me a PDF after the show?” She stares at me like I’ve just asked her to strip down in the middle of the Javits Center.

The truth is, book publishers still aren’t sure what to make of digital publishing. BEA 2013 boasted a “Digital Discovery Zone,” but for every business aimed at revolutionizing delivery to consumers, there were two whose purpose boiled down to making the digital landscape less frightening for hidebound publishers.

My friend and I pool our resources and discover that, between the two of us, we’ve found only four publishers offering digital swag after two full days on the convention floor. Of those, half are for audiobooks and all require a lengthy online registration, a process far less convenient than snatching a book off a stack on the show floor.

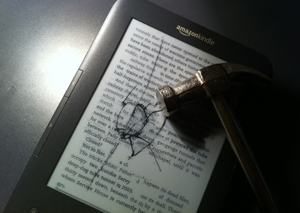

While readers have enthusiastically embraced digital publishing, the book industry itself has continually dragged its heels. Even those who’ve embraced digital review platforms like NetGalley have been reluctant to make similar leaps for retail sales of digital books, and their reticence has limited consumer access to digital titles, particularly backlist–the same books consumers have the most difficulty finding in print. Add in the fact that many day-and-date releases cost nearly as much as their physical counterparts, and the e-market, while substantial, seems unlikely to take the place of print anytime soon.

Some of the problem stems from tradition. The people drawn to publishing as a professional are, by and large, book lovers, and as such, often as attached to books’ physicality as to their text. More is paranoia: unlike music, whose digital age developed largely in response to an already thriving pirate industry, book publishing has held back, waiting for reliable DRM that seems unlikely to materialize.

On some levels, their reluctance is pragmatic. The technology of digital publishing is awkward and inconsistent. The closest thing to a single file standard, e-pub, is still far from platform-agnostic and notorious for destroying formatting elements, which limits what writers and designers can do structurally if they’re planning for digital.

And that’s just for text-based books. Options for visually intensive publishers are narrower still, and even more platform-dependent. Formatting highly visual material takes resources and technical savvy that can make the process cost-prohibitive for smaller publishers. Rapidly changing technology, varied platforms, and lack of standards makes digital development a risky investment even for larger publishers.

The result is an explosion of third-party packagers, businesses that hold publishers’ hands through the process of digital conversion and retail. They, too, are frank about the limitations of the media and the impossibility of fully automating the conversion process. Les Csonge, co-founder of cloud publishing platform YUDU, told Wired that his biggest challenge is dealing with hardware. With no single standard format to make content platform-agnostic—a must for breaking into the lucrative and elusive education market, for instance—reaching a wide range of readers is a matter of laboriously reformatting any given title for each individual platform.

Real progress on the digital front would require companies like Apple and Amazon to collaborate to create a consistent format – and for now, they won’t, thanks to a combination of paranoia and proprietary and competitive concerns.

That means that any publisher who wants their books available on, say, iBooks, Kindle, and Nook will be facing three different formatting standards, not to mention content restrictions—and, often, entirely new economic models. In print publishing, publishers set prices, but in digital publishing, the power lies with the retailers. This is especially true for Kindle and iBooks, whose strict pricing guidelines have drawn criticism from both publishers and consumers.

For Csonge, the future of digital books lies with hardware developers, specifically multi-use tablets—cloud-friendly devices that can support multiple modes of media and publishing platforms—and smart phones. While apps don’t entirely solve the problems of cross-platform compatibility, they’ll at least allow readers–and publishers–more software versatility. on any given device.

“Even here [at a book expo], you don’t see people carrying around tablets,” Csonge told Wired. “But everyone has a phone.”

By Rachel Edidin 06.05.13